David Tovey - Mastering The Art Of Staying Alive

- Stephanie Whalley

- Nov 20, 2020

- 12 min read

Updated: Jul 31, 2021

Catch the conversation here: Mastering The Art Of Staying Alive

This weekend was the second weekend of Lockdown 2.0 in the UK. Now, I’m a homebird who like’s being curled up under a blanket at the best of times but even I’m sick to the back teeth of social distancing, curfews and staying indoors unless absolutely necessary. I spent my Sunday morning griping about not being able to go Christmas shopping or out for a nice meal, from the comfort and sanctuary of my warm, loving family home, with the subconscious reassurance of my own good health. Touch wood.

I was bored. I am bored but sometimes, boring makes for the best kind of story. Humdrum, run of the mill and uneventful. For me, I prefer the stomach-lurching twists, turns and cliffhangers to stay in the fictional novels I pour over before disconnecting from the plots and piling them up on my bookshelf to collect dust.

For our next guest, David Tovey, a strong dose of tedium would likely have been wholeheartedly welcomed at many points along life’s way. David’s narrative thus far unravels with a shocking number of plot twists - a story of unbelievable adversity and unlikely survival that you would never imagine could possibly manifest as somebody’s version of real life.

As always, it’s a true and humbling honour to be sharing this story on our platform and I can’t express just how strongly I urge you to stick the kettle on, sit comfortably and absorb every single word of it. Writing this story came at the perfect time for me, knocking my perspective back into touch and I think more of us could do with that kind of wakeup call from time to time.

“Food literally brings communities together and I loved it; I loved everything about being a chef”

Today, David Tovey is an artist, an educator and an activist who has cooked for the Queen, headed up the BFI kitchen and had his own creative event at the TATE Modern. He is the founder and artistic director of the One Festival of Homeless Arts, which was conceived after David was invited to take up an artist’s residence at the renowned Diorama Arts Centre. A pretty impressive profile but a position which has by no means whatsoever, been a smooth and linear ride to success.

Along the way, David has battled with his sexuality, drug addiction, homelessness and a variety of life-altering diagnoses, all under the veil of a “societal structure which is broken” and the lasting effects of youth in the British Army. So, in order to do this story justice, let’s take it back to the very beginning, to a 16-year-old David who followed in his father’s and grandfather’s footsteps in joining the military as a chef.

Cheffing had been something that sparked David’s interest after finding himself a weekend job as kitchen porter at the age of 13. The decision was motivated by a desire to earn the kind of money that his parents of seven children couldn’t afford in order to keep him in the luxuries and labels that his peers at his school in Tunbridge deemed prerequisite to social acceptance. Three years later, David joined the British Army as a means of acquiring the skills and training in cheffing that he couldn’t afford to do through standard qualifications.

“A young 16-year-old who hasn’t gone through puberty, within weeks, was being taught to kill people - that’s not normal”

During his time spent in the army, David was stationed at Sandhurst for a while, cooking for members of the Royal Family who were going through training, as well as various princes from around the world. Befriending kitchen comrades who are now some of television’s most celebrated chefs and preparing canapés for the Queen and her entourage, you could be easily led to believe that this was a glamorous move for our guest. However, being an army chef isn’t all about finessing mille-feuille or learning how to master a soufflé at leisure because of course, joining the military also comes hand-in-hand with a degree of brutality.

“A young 16-year-old who hasn’t gone through puberty, within weeks, was being taught to kill people - that’s not normal”, David recalls as well as explaining how “when you join the army, they break you as a person to begin with” to then “remould you”. From cleaning the ablutions to learning how to kill and rigorous 100-hour working weeks, joining the army was a shock to the system and something which has left our guest with “lasting traumas” that he holds largely responsible for the problems he has faced since - and still faces today.

Over the course of his career in the army, David describes how, “I was starting to figure out who I was and my identity” and with that came the realisation that he was gay. At the time, homosexuality was illegal in the British Army, so David was presented with a dilemma and a pinnacle crossroads in his story. “I’m either going to be found out or forced out”, he remembers thinking and how he was eventually “pressured and pushed out”, leading to his resignation.

Suddenly, all of the pain and trauma he had endured so far to serve his country was met with total condemnation for who he was as a human being.

“I felt like I was moving back to a country I was still angry with”

Following David’s departure from the army, he spent two-and-a-half years in Australia, further discovering his identity and developing his culinary craft. Unfortunately however, the time came when his visa could no longer be extended and so David embarked on the journey back to his homeland of Kent, despite feeling like he was “moving back to a country [he] was still angry with”. Angry for chewing him up and spitting him back out, based purely on his sexual orientation and unwillingness to sacrifice who he knew he was deep down.

Less than two weeks after landing back in Kent, David’s best friend (and acclaimed chef) James Tanner invited him to stay in Plymouth with him for a while. The following day, David successfully interviewed for a job as a chef with James’ brother, a move on the chessboard of life’s great game that eventually catalysed a move to London with James to open up their own restaurant. Two restaurants in fact, the food-side of which David owned and the bar-side of which James owned - one in Euston and one in Highgate. On the menu was traditional British fare - brasserie-style - with colourful influences from David’s time spent cheffing Down Under.

On Easter Sunday of 2011, David was walking to the Highgate restaurant from his home in Holloway and started to feel decidedly unwell. He recognised his worsening symptoms as those of the strokes his dad had had and sure enough, minutes later he was in the back of an ambulance with slurred speech and a drooped face being rushed to hospital. David recalls how the ambulance had been in the vicinity at the time of his call and within 2.5 minutes of him hanging up, he was being tended to by paramedics and blue-lighted to safety. One of many instances during our conversation that David refers to himself as being “really lucky”.

“I went into a park and took a fatal overdose at 8 o’clock in the morning”

David was treated for the stroke but in the chronology of his life, it marked “the start of everything going wrong”. Left with residual cognitive damage, David began to blame the pressures of the job and began drinking a lot in order to “self-administer relief for the stress”, eventually walking away from the two businesses he had opened with his best friend only three years previously. This snowballed into him also losing his home and his partner and just when you thought one human couldn’t take anymore, he was also diagnosed with neurosyphilis - a sexually transmitted disease which invades the spinal fluid and brain.

They say bad things happen in threes but David had almost lost count by the time he was later diagnosed with colon cancer during an intense treatment plan for the neurosyphilis. Ten days after his cancer diagnosis, the nurse administering David’s penicillin injection (prescribed as part of the neurosyphilis treatment) hit a splinter nerve, accidentally injecting the formula straight into David’s veins, “causing some sort of cardiac arrest thing”. What then ensued was what David describes as a “nervous breakdown” and five suicide attempts in one week.

Fortunately, none of these suicide attempts were successful but a cruel twist of fate once again emerged from around the corner, seeing David diagnosed as HIV positive. The initial diagnosis felt like “the world had just crumbled under [his] feet” but then with an answer as to why he had been feeling so ill for the past few months, David told us how life finally started to get a little better. He enrolled onto a Fine Art course at London Metropolitan University and in 2012, started making socially engaged work around his HIV status. In a rather eerie foreshadowing of a future unknown, David also created a film about homelessness as part of his ongoing creative studies.

“When we say homeless, we automatically have that image in our head of somebody sat in the street with a begging card and a cup, or stuff like that - that’s 2% of the overall problem of homelessness”

Towards the end of his foundation year at university, David started to become more ill and counteracted the mental strain of that with yet more alcohol, drugs and self-administered painkillers. He wasn’t paying the rent and became increasingly anxious about the legitimate concern that his flatmate would eventually wind up losing her home as a direct result. The mounting pressure of his situation led to David making his sixth suicide attempt, taking a fatal overdose in a public park, only to be brought back around from the limbo between life and death by a lifeguard on his way to work at the local swimming concourse.

David was taken to hospital, “angry to have survived” and then returned back the flat to find that the locks had been changed. Suddenly, even after everything that had come before, David found himself homeless. His “ex-soldier pride” instilled in him the mentality that “I got myself into this so I can get myself out” and so David moved into his Peugeot 206 with no access to funds thanks to a Thatcher government which ruled that students weren’t applicable for job seekers’ allowance. All he had was the odd ten pounds sent over by his mum and a camera and laptop, which he hid securely out of sight.

For five long months, David ate out of bins and tolerated abuse from a society which “doesn’t view homeless people as humans”, occasionally sourcing bits of old furniture and crockery to exchange for a pittance from a guy with a shop in Holloway. His health deteriorated, he stopped taking all of the necessary meds and his weight plummeted to a dangerous 64kg; David felt let down by the country he had served when he most needed the help from it. Hope started to dwindle, David hadn’t eaten for three days and he simply “couldn’t see the following day”, so picked up a lethal dose of crystal meth to end his life.

“I found that the camera became a mask for me and it meant that I could approach people and take photos […] and start to see the beauty of London as a homeless person”

Sitting on yet another park bench with a needle poised to inject a fatal measure of narcotics into his veins, David was interrupted by a park enforcement officer who shouted over “what are you doing?”. This park enforcement officer named Gavin sat on the bench next to David and listened whilst he poured out his troubles, crying inconsolably and “rocking like a mad man”. Gavin bought David some food, gave him a bit of money and booked him into a homeless shelter, but what David believes was the most invaluable thing this man on the bench had given him was choice - the opportunity to choose another chance at life.

Gavin gave David the address of the shelter and left him with the responsibility of choosing between a new life or the death he had previously been chasing. David chose the former, eventually finding his way back to the car and onto the homeless shelter supported by The Pillion Trust - a grassroots charity who come to the aid of homeless people in Islington. He was welcomed with a cup of tea, a slice of cake and a much-needed chance to sit down and take stock. The shelter put David in touch with Veteran’s Aid who eventually got him moved to a homeless hostel in Camberwell, run by a charity called West London Mission, along with support for his health and HIV meds.

So, let’s just recap for a moment here before we continue…

At this point, David has been through the army, come to terms with his sexuality, suffered a stroke, been diagnosed with neurosyphilis, colon cancer and HIV, walked away from his businesses, been homeless and tried to end his life seven times. It’s safe to say that - call it fate, destiny or whatever you like - this human being was always meant to stay alive.

It’s no coincidence that David Tovey is still here to tell this story, I don’t care what anybody says. David accredits a lot of his survival to luck but from where I’m standing, luck isn’t what saved him - luck simply stepped in at the right times to provide David with the opportunity to exercise his own strength and fend for his survival himself.

Perhaps one of the main reasons David was always meant to survive, despite all of the odds stacked against him, was the One Festival of Homeless Arts he founded in 2016…

During his stay in the homeless hostel, David decided to continue on with his artistic endeavours. He could no longer study at university, forced to choose between housing or his studies, but wanted to keep his mind stimulated. He created art in all manner of mediums (installation, film and photography mainly), assigning himself personal projects to keep in contact with the art and culture which, during our conversation, he dubs as “a human right”.

“I’ve been really lucky to have my work shown and that feeling I have when my work gets seen in a gallery space is magical”

Following an interview with Patrick Strudwick at The Independent, David was contacted by a group called Clothing the Homeless and asked to design a t-shirt to be sold online. Wanting to make the artwork more than just a digital transaction, David taught himself – via a YouTube tutorial - how to make couture-style clothing. What later transpired was a fashion show on the Southbank entitled ‘Man on the Bench’ - “named after Gavin, the man who saved my life”, David tells us.

During the event, David got talking to a guest about what he was doing, explaining that: “It’s pointless me standing on a soapbox getting angry and preaching about homelessness because people are just going to walk past and ignore it, like they ignore people when they’re sat on the street. But if you get a load of beautiful models - male and female - wearing all these couture, mad clothes made out of recycled materials, people stop and look and want to know what it’s all about”.

That guest turned out to be the Deputy Arts Editor for The Economist, who later featured David on a podcast which reached a whopping 5 million listeners. In quick succession, David also got invited by The Museum of Homelessness charity to run an event at the TATE Modern, as well as being invited to be an artist in residence at the Diorama Arts Centre.

For his Diorama exhibit, David decided to showcase the work of other homeless people to give them a chance at the feeling and exposure he had already been afforded, inspired by an event he had been at with Arts and Homelessness International. That altruistic idea back in 2016 transformed into what is now the One Festival of Homeless Arts - showcasing the work of homeless people from all over the world, purely funded by donation. The festival has since been featured by the BBC and is now looking forward to employing its first Chief Executive as the brand is steered towards a new name, a new direction and a new, and bigger, venue.

“I have decided to stick with love, hate is too great a burden to bear”

As with all of our guests we asked David who or what is his greatest inspiration, to which he, quite clearly, referenced his Man On The Bench, Gavin. He also told us about how he finds an incredible amount of inspiration in certain communities, particularly the black community and the trans community who are “victimised and abused every day”.

On the topic of Black Lives Matter, David explains that “seeing how the world has come together around this movement literally lifts [him] up” and how he finds empowerment in these communities’ grit and determination to never give up at the hand of hardship. I wonder if David knows just how much his own subscription to that precise mantra of courage and conviction is inspiring and uplifting for those around him, for people just like us…

David’s ultimate inspiration however, is Martin Luther King Jr. and more specifically, his famous quote: “I have decided to stick with love, hate is too great a burden to bear”. “I live by that every single day”, David tells us and as I listen to him, I think to myself what a damn shame it is that more people don’t follow in those very footsteps. If we all decided to let love take the forefront a little more often, perhaps society would start treating homeless people as the human beings they are, and perhaps less people would need their lives saving from suicidal attempts by passersby in the park.

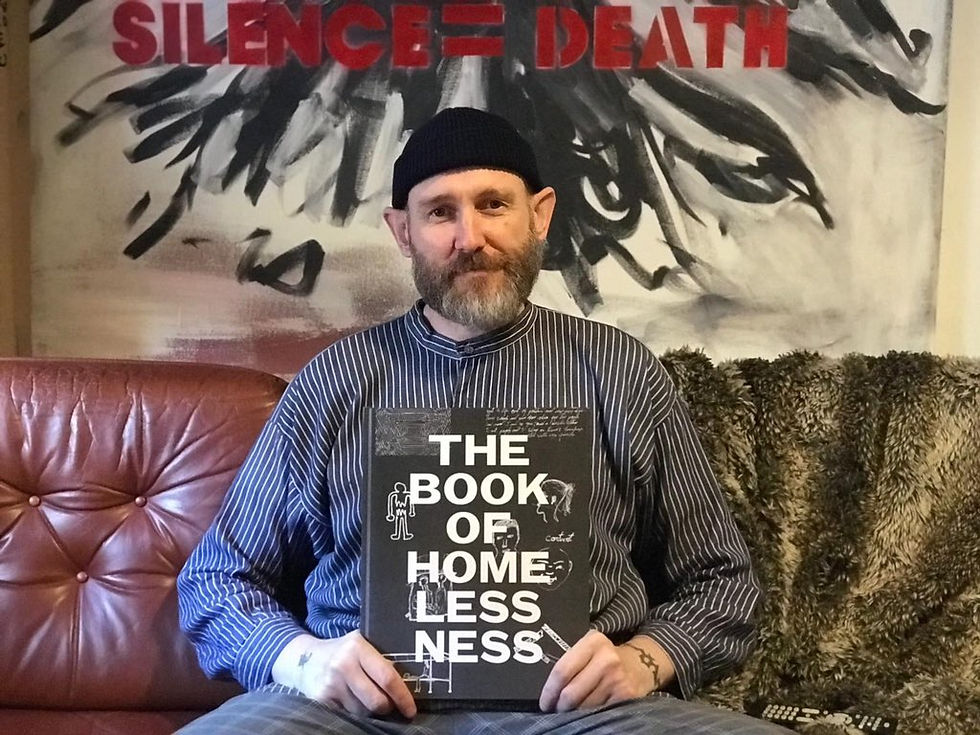

To see David’s latest work, ‘Unknown Solider’ - a part biographical, live performance about a veteran who takes his own life - head over to davidtoveyart.co.uk. To stay in the loop with all things One Festival go to onefestivalofhomelessarts.com, and to discover more about Accumulate and The Book of Homelessness project that David contributed to click here. To hear more about David’s incredible and moving story, make sure to catch up with his episode on the ONEOFTHE8 podcast.

Comments